Introduction: Carnival as a Cultural and Operational Paradox

Notting Hill Carnival is a paradox. It is both a celebration of identity and a crucible of public safety. It is a free, open-access event that draws over two million people into the streets of West London, yet it operates without the formal controls that govern most major public gatherings. It is a symbol of multicultural Britain, but also the single most resource-intensive and risk-laden event in the UK policing calendar.

As a former Chief Inspector with thousands of hours operational command experience across countless public events from rural festivals to high-profile protests, I’ve seen the full spectrum of risk. My time at the National Policing Operations and Coordination Centre (NPoCC), attending strategic planning meetings in SO22 at the old Scotland Yard, gave me a national view of event risk. But few events compare to the scale, complexity, and contradictions of Notting Hill Carnival.In 2015, I shadowed the Bronze Commander on the ground at Carnival. It was a formative experience. I had first attended Carnival as a 10-year-old, and over the years, as I lived and worked in London, I returned many times. My father, a site foreman in the 1990s, had also often lived and worked in London during the week, so attending Carnival was part of my own cultural landscape. Yet even as a child, I vividly remember the shift in atmosphere as the day turned to late afternoon. That feeling of unease and of heightened tension and it never left me. It was the time in the day, even when a thrill seeking, risk taker like my dad would suggest we take our leave. Years later, as a seasoned officer with a finely tuned radar for danger, I felt it again.

Carnival is vibrant, powerful, and deeply important. But it is also, undeniably, a public safety anomaly.

The Cultural and Political Significance of Carnival

To understand Carnival’s operational challenges, we must first understand its cultural and political weight. Carnival is not just a party, it is a legacy. Its roots lie in resistance: born from the racial tensions of post-Windrush Britain, it was a direct response to the 1958 Notting Hill race riots. Trinidadian activist Claudia Jones organised the first indoor Caribbean Carnival in 1959 as a celebration of Black identity and resilience. The first outdoor event followed in 1966, led by community activist Rhaune Laslett, who envisioned a multicultural street festival to unite the area’s diverse communities.

Over the decades, Carnival has become a cornerstone of Black British identity and a powerful expression of multiculturalism. It is politically untouchable. To criticise Carnival is to risk being seen as anti-diversity, anti-community, or worse. Even when public safety concerns arise, political leaders tread carefully. The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has consistently defended Carnival as a vital celebration of Caribbean culture and London’s diversity, calling it “the biggest festival of inclusion and diversity the UK has, if not Europe.”

This political shield makes Carnival unique. It is the only event in the UK where the acceptance of health and safety risk is not only high, it is institutionalised.

Commanding Carnival: Risk, Reality, and the Licensing Paradox

Notting Hill Carnival has to be the most complex public safety operation in the UK calendar. The scale is staggering: over two million attendees, hundreds of sound systems, and a footprint that spans a densely populated residential area. Planning begins months in advance and involves a vast network of stakeholders, including the Metropolitan Police, London Ambulance Service, London Fire Brigade, Transport for London, local authorities, and community representatives.

At the heart of this operation is the Gold Commander, who sets the strategic direction and oversees the event through the lens of the National Decision Model (NDM) the UK’s ethical and intelligence-led framework for policing decisions. The NDM is not theoretical at Carnival; it is lived in real time. Intelligence is gathered from historical arrest data, crowd modelling, threat assessments (including knife crime, gang activity, and sexual offences), and community sentiment. Risk assessments identify high-pressure zones such as bottlenecks and sound system hotspots, and contingency plans are drawn up for crowd dispersal, emergency access, and tactical reserve deployment.

Despite this meticulous planning, the operational reality is sobering. Between 2002 and 2025, there were *5,395 arrests at Carnival. These include 121 assaults on police, 163 incidents involving offensive weapons, 199 cannabis-related arrests, 64 for Class A drugs, 88 for drug supply, 12 robberies, 8 violent incidents with injury, and 56 sexual offences. Since 2014, there have been nine reported rapes and four recorded murders. In 2025 alone, 334 arrests were made, with 172 categorised as “other” a catch-all that often includes public order offences, theft, and obstruction.

This data presents a stark contradiction. If Notting Hill Carnival were a new event proposed to a Safety Advisory Group (SAG) today, based solely on its historical record, it would almost certainly be refused a licence. No other event in the UK would be permitted to proceed with such a consistent and well-documented risk profile. The licensing threshold for public safety, crowd control, and crime prevention would not be met. And yet, Carnival continues, not because it is safe by conventional standards, but because it is politically and culturally untouchable.

This is not a call to cancel Carnival. It is a call to acknowledge the impossible position it places on those tasked with keeping it safe. The event challenges every principle of modern event planning: predictable crowd flows, secure perimeters, controlled ingress and egress, and manageable risk. Carnival has none of these. It is open, sprawling, and deeply embedded in the urban fabric of West London. The very things that make it culturally authentic, its spontaneity, its street-level intimacy, its community ownership are the same things that make it operationally volatile.

There is no other event in the UK where the acceptance of health and safety risk is so high, or where such risk would be tolerated. Glastonbury, for example, is a ticketed, fenced, and professionally managed site with a robust licensing regime. Even large-scale protests, which carry inherent unpredictability, are subject to strict conditions and often rapid police intervention. Carnival is different. It is not just an event, it is a legacy, a symbol, and a political statement. And that makes it uniquely difficult to manage, critique, or reform.

The Hidden Cost of Policing Carnival

Policing Carnival is a monumental task and I still have a lot of respect for those that do it. In 2025, it required 168,000 officer hours over two days, using a (out-dated) Special Policing Services figure of £63 p/h per cop for the reported figure of 7,000 additional cops per day working for 12 hour shifts being required to police the event, it would be an estimated £10.58 million to police. That is also to ignore the real cost inclusive of the thousands of hours planning, the logistics and welfare costs for food and refreshments for the officers likely to be pushing the figure much closer to £12M. These costs are largely unrecovered. Officers working rest days are owed time off, which must be scheduled within three months. This creates a ripple effect: neighbourhood teams are stretched, investigations delayed, and community engagement deprioritised.

While the Metropolitan Police can probably absorb this strain, smaller forces would struggle. A Carnival-scale deployment in a rural or regional force could cripple local resilience. The operational burden is real, but it is rarely discussed publicly.

Holding Two Truths

Notting Hill Carnival is both a cultural jewel and a public safety nightmare in my own view. It is a celebration of heritage and a test of operational resilience. We must be able to hold both truths. Those in power probably need to protect its legacy but have an absolute responsibility to protect the people who attend and police it. That means honest conversations about funding, planning, and reform without fear of political backlash.

However, I’ve long held the personal view that policing, particularly at the senior command level has always been too reluctant to push the public safety agenda when it comes to Carnival. Not necessarily out of negligence or lack of professionalism, but because the political sensitivities surrounding the event make it almost impossible to do so without consequence. I’m not criticising that reality; I understand it. But while I was in the service, airing these kinds of views publicly would have been unthinkable. And yet, these are conversations I’ve had hundreds of times with Met Public Order and Public Safety commanders, many of whom feel exactly the same way. There is a shared understanding that Carnival presents a unique challenge, one that tests the limits of operational tolerance and political diplomacy.

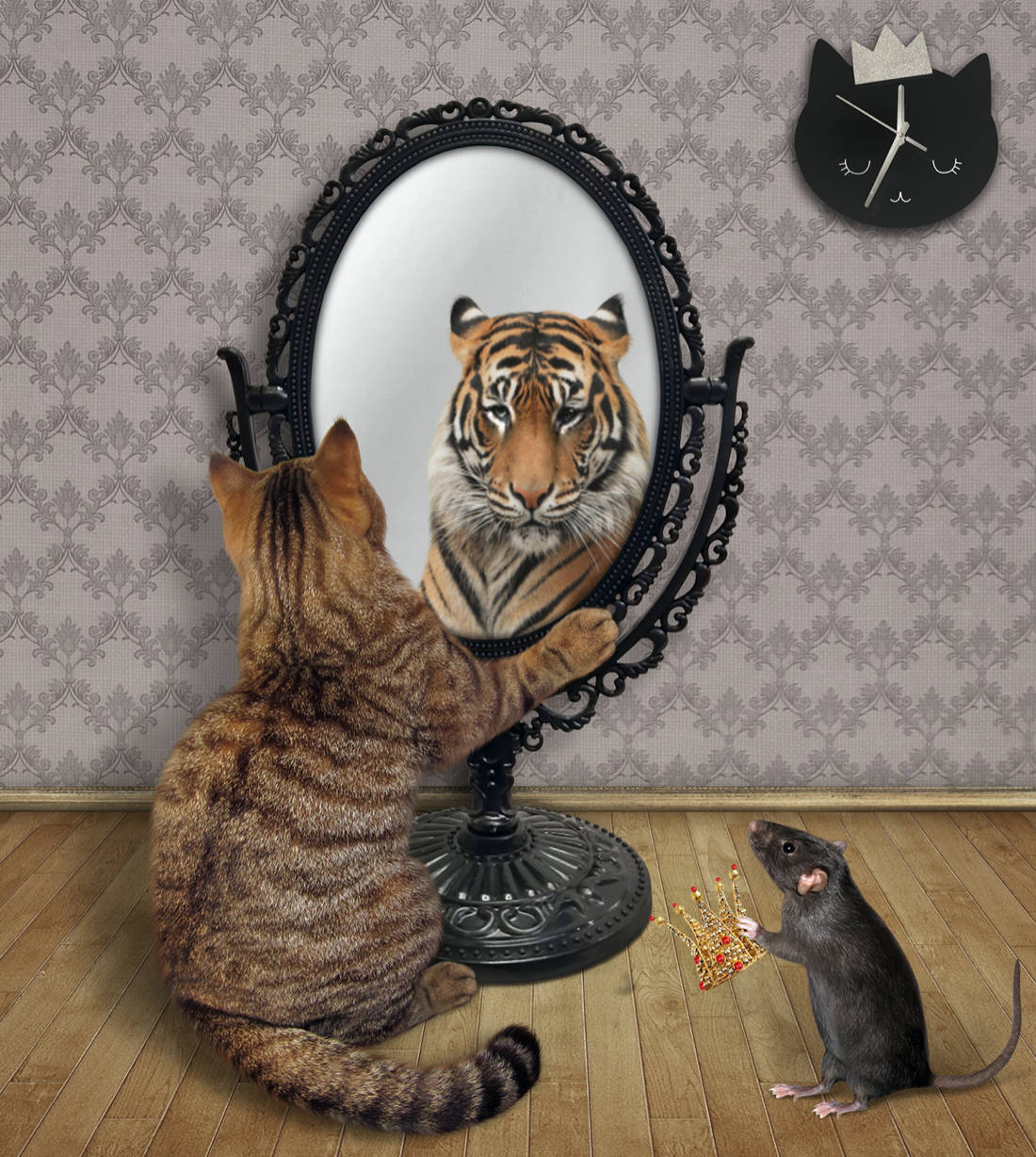

Carnival is not just a party. It is a mirror of Britain’s past, present, and future. And like all mirrors, it reflects both beauty and complexity.